That Movie

Then she told me a story, about my father. A story that made me cry at the time, although I did not know why. Maybe, maybe, maybe because I was sad of what happened to my father, what he experienced. Or maybe I was old enough to understand that we did not control our own fate. Not me, my father, not even my mother. That we could be separated at any time.

Ratrikala Bhre Aditya

#1965setiaphari

#living1965

Father

Then I became an adult and started reading critical texts about the New Order, particularly about the 1965 events. I remember I felt very angry – I had been lied to for twenty years. When John Roosa’s book was banned in Indonesia and its online version became available, I bought it. I planned to print it and give to my father as a retirement gift. I hoped that finally we could talk about the 1965 events and his youth in Tulungagung.

My mother then told me that my grandfather was imprisoned for three days during the 1965-66 chaos. This was because he once went to the Soviet Union, a trip paid for by the Indonesian Textile Cooperation, and because he was a member of the Indonesian Nationalist Party. My mother brought him food and clothes for the time he was in prison.

“Why did you and Grandmother never tell me?” I asked.

“Why?” she replied. “My father was released three days later and that’s in the past. I wouldn’t have remembered that he went to jail if you hadn’t asked.”

Apparently it is true that violence during that time had been normalised by history.

My Dad finally retired but I never gave him the book. When he left us and when we finally met a few years later, he still did not dare to look me in the eye.

Wulan Dirgantoro

#1965setiaphari

#living1965

West Papua, 1965

What was meant by “safeguarding” was the launching of massive military operations across West Papua, and the suppression of a Papuan rebellion in Enarotali in the Central Highlands after Sarwo Edhie’s plane was shot at by a group of Papuan police. As reported in the New York Times, Indonesia denied that it had bombed civilians but evidence supports that Indonesia indeed had used rockets and targeted civilians. But who cared? Who cared what happened in Enarotali then and in the years that followed? Who cared what happened in Biak and Manokwari in 1965 and the years after?

Two months before the so-called the 30th September Movement and the subsequent persecution of leftists that followed, thousands of Papuans were killed by the Indonesian military in an operation called “Operation Awareness”. According to al Rahab (2006), the operation that took place under the command of Brigadier General R. Kartidjo was concerned not with Papuans’ “awareness” — that they were part of Indonesia — but instead, it was aimed at the crushing of West Papuan organised resistance towards Indonesia which had emerged in July 1965. The Indonesian military called the resistance the Free Papua Organisation (Organisasi Papua Merdeka or OPM in Indonesian), even though there was no such thing as an organisation.

A few years later the generals changed their minds and the armed groups of Papuans were called “wild security disturbers ” and after that “movement of security insurgents.” Today they are also called “group of armed criminals.” The general opinion of the Indonesian military is that Papuans have no other motive than to become insurgents or criminals by burning the headquarters of the military. In a 1996 interview with the periodical Gatra, Retired Lieutenant Colonel D. Tandigu said that the Free Papua Movement was not motivated by nationalism, but just by frustration.

The question is why then has Indonesia never been able to address the frustration of the Papuan people. If it were just a psychological state, Papuans would have changed. They would have been content with being a part of the Indonesia. Indonesia claims it has liberated Papuans from colonialism, that it has uplifted them from their “barbarian and primitive” past. Why is it then that Papuans have never felt free under Indonesia? For Indonesians, it is a difficult question, is it not?

Veronika Kusumaryati

#1965setiaphari

#living1965

This Film

My parents always said: “don’t think too much about it. It’s just a movie.” After the second and third year of junior high school, I started reading books and it was only then that I understood my parents’ intentions. They were trying to counter the New Order propaganda in a very subtle way. They were trying to say that the contents of this movie were wrong, but not in a direct way as they were afraid that I, a child, would tell my teachers, which would have gotten me in trouble. It was only after my teens that my parents, particularly my mother, became more open to discuss the events of ’65 with me.

I was lucky to have parents who could counter New Order propaganda. But not all children were as lucky as I was. Many children grew up believing the lies of New Order.

And now, 19 years after reformasi, my experience (and of all children of my generation) is repeating with many small children in this country. May they also be saved, just like me. I really hope so.

Dhyta Caturani

#1965setiaphari

#living1965

Elections

One afternoon, I was helping my father in the garden when he went to get mail from the letterbox. He returned looking rather puzzled, but with a smile on his face. “Look,” he said, “a card so Papa can vote!”. Probably at the time I did not exactly understand why that was so special, and I can’t remember that my Dad said anything about it. But instinctively I knew it was extraordinary – in Indonesia, my father was not allowed to vote.

When election day came, my Dad took me with him as he cast his vote. As long as I can remember, he never missed a chance to do so. He was able to enjoy that right in a country that was not his, while the country of his birth denied him to do so.

And every time I get a chance to vote, I do. And I think of that afternoon, when the flowers bloomed.

Ken Setiawan

#1965setiaphari

#living1965

The Faces of ‘65

Father worked his life in the P&K, the Department of Education and Culture, a member of Korpri, the corps of government employees, and voted for Golkar (Suharto’s party) of course. Mother, a member of Dharma Wanita, the corps of government employees’ wives. I regard the book “30 years of Independent Indonesia” as Father’s most precious estate. The authority of the Orba doctrines is crystal clear in my family.

However, when I claimed the book as my property (none of my siblings refuted my claim), I actually had a different awareness already. I was raised within the version of Orba’s history, and when I matured, I looked for something else.

As far as I remember, my sensibility changed when met with literary works, amongst others by Umar Kayam and Ahmad Tohari, which “gave face” to the tragedy of ‘65. I believe that Orba’s success was in dehumanising anyone alleged to be involved with the G30S. Then, these writers show that they are really human like us. Someone’s wife, someone’s husband, someone’s child, someone’s father, someone’s mother, with a heart, and feelings. This astonished me. How could history rub so many humanly faces out of so many people, for so long?

Heru Hikayat

#1965setiaphari

#living1965

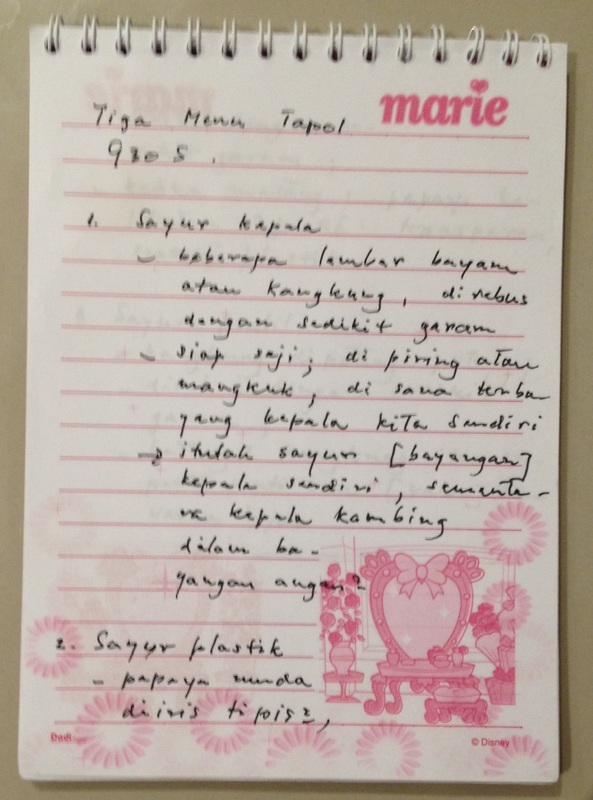

Recipes

They are “head vegetables”, cooked in so much water one could see his or her reflection; “plastic vegetables”, because the young papaya was cooked so long it resembled plastic; and “valve vegetables”, because the stalks of the water spinach looked like tyre valves. When I got the note pad, I did not consider cooking these recipes.

But some time ago, my daughter asked me what kind of food was given to her grandfather while he was in prison. Maybe one day I should try the recipes, so she will know.

Ken Setiawan

#1965setiaphari #living1965

Buru’s First Harvest

Sri Nasti Rukmawati

#1965setiaphari #living1965

Breaking the Chains of Silence

The esteemed Dr. Erwan Agus Purwanto, Dean of the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences of Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta.

The esteemed Dr. Hilmar Farid, Director General of Culture at the Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia.

Esteemed teachers and academic community of the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences of Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta.

Esteemed guests.

Today is an important day for me, as I am coming “home” to my alma mater, the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences at Gadjah Mada University. Previously, it was known as the department of Law, Economy, Social and Political Science. It was situated at Pagelaran, at the northern town square (alun-alun utara). After fifty-one years “the lost son” has been found by his “mother”. Fifty-one years is truly a long time in history. And that can even be longer if we do not act, if we do not dare to take a step to break the chains of silence.

I thank the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences of Gadjah Mada University, and in particular the Dean, who has taken the responsibility to resist the efforts of forgetting, which are ongoing. For fifty years, we have been made part of a political system that has enforced that which should be remembered and that which should be forgotten – to the extent that we have lost our awareness and our memories of the past. Both of which are very important to rebuild life today.

This award is not for me, but for the hundreds of friends who disappeared and did not return. This award is also to remember and to give a voice and dignity to the victims of 1965, in an effort to express the truth, to rehabilitate and reconcile.

I thank my wife and children who, with love and mutual affection fight together in a pilgrimage for humanity, to spread the seeds of civility and justice.

I will end with a poem for my late friends Ibnu Santoro (lecturer at the Faculty of Economy) and Sunardi (lecturer at the Faculty of Pedagogy), as well as the students of Gadjah Mada University, who disappeared in 1965 and 1966.

Hersri Setiawan

#1965setiaphari

#living1965

Coming out

That day, I had lunch with ten of my friends from Uni. I remember our bonding activity was to rant about Soeharto, and even five years after the fall of his regime, that still felt relevant.

Suddenly, without much thoughts, my big mouth defeated my brain and I blurted out. “My grandfather was disappeared in 1965.” Immediately, I felt I wanted to disappear. My heart beat so fast and so loudly as though it was venting all its opinions just before dying. The first rational thought that came to my mind was, “Who amongst these people will kill me now?”

A few seconds later, someone from the opposite side of the table uttered, “My grandfather, as well, was in prison, but he was released.”

I knew these people for more than 12 years by then. No one amongst us has talked publicly about 1965 before, and within a few seconds that day, two out of ten came out.

How many more of us are there?

Tintin Wulia

#1965setiaphari #living1965