A piece of cloth

Mrs Sunardi was released before I was from Bastion. When she was released, she gave me a handkerchief. She told me her husband had given it to her as he was taken away from Fort Vredeburg forever. She told me to keep the handkerchief, because she could not do so herself. “Take care of it, Dja!” she said as she embraced me, crying. I took the handkerchief with me wherever I went, to Buru and when I came home in 1979. I have looked after that historical square piece of cloth, until today.Tedjabayu Sudjojono

#1965setiaphari #living1965

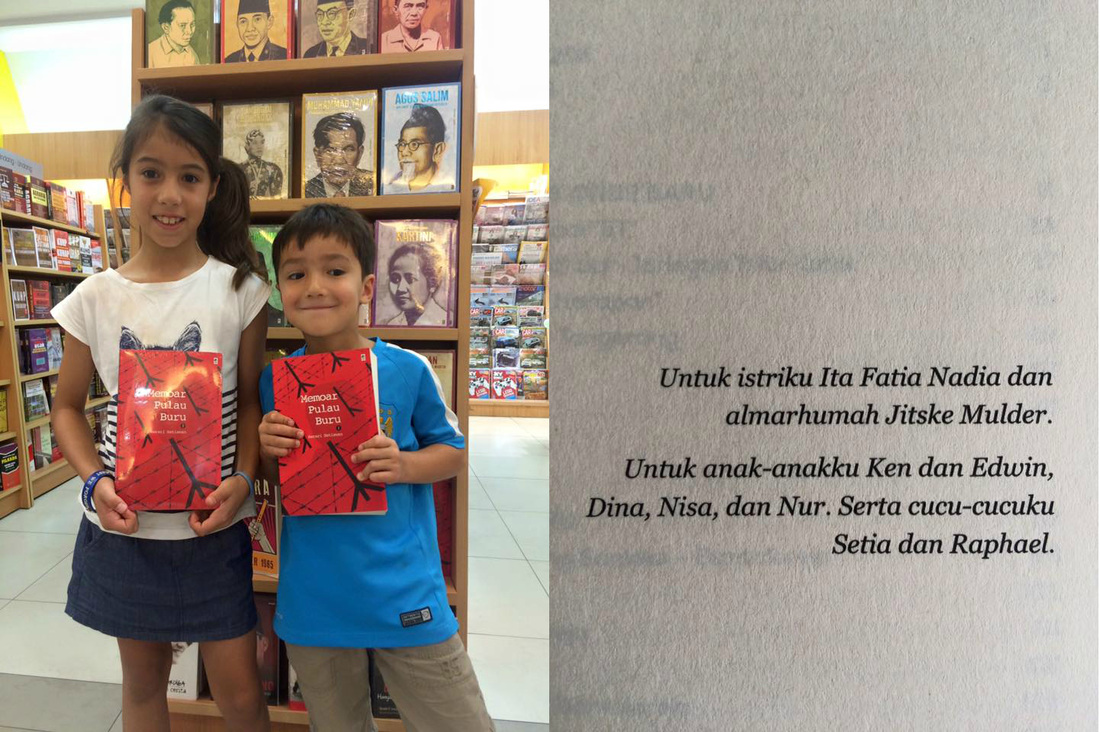

Grandfather’s Book

For a very long time, all I wanted was an ordinary family. This is the family I was born into and the one I received. It’s extraordinary. Today, my kids walked into a bookstore and found their grandfather’s book, which is also dedicated to them. They may still be too young to completely understand their grandfather’s history and what it means to our family, but one day they will – because he wrote it down. His story is their story. As a family we are stronger because of it.

Ken Setiawan

#living 1965 #1965setiaphari

Where is Grandpa?

Something happened around 1984, when I was about 8 year-old, third grade, and I always remembered it. One day, father and I were looking through our family’s photo album. When we stumbled upon a significantly larger photograph of grandpa, father told me, “If you see this man when you’re on a bus, or when you’re walking, quickly call him, okay? Tell him that you are his grandson, the son of Bima!” I was confused, and I said, “Really? But grandpa has passed away, right?”

This question apparently struck father and he then kept silent. Only now I can understand the context: that father has always been hoping to find grandpa alive. This is what differentiates a missing subject and a dead one.

Rangga Purbaya

#1965setiaphari #living1965

Indonesia since ’65, Papua since ’63

At one point, my father told me about my grandmother’s younger siblings. Her sister, it turned out, was a Gerwani partisan. She was an excellent dancer, he said. I know her, she’s still alive. But her brother – he was missing, they don’t know where he is. It turned out that he was the leader of the Pemuda Rakyat organisation, either for the whole Bireuen or for our village, if I didn’t misunderstand.

My father’s story made me really want to talk with grandmother. I went to her room, and she told me, “My brother was really handsome, and so kind, and people really liked him. I don’t know where they took him to. He was getting prepared to get married. I also don’t understand why our fellow villagers suddenly got so angry and hateful towards him, and then he was just missing. I don’t know where he is, until now. How can people be so?” Her eyes were watery. I just hung my head.

I told her, “Grandma, now a lot of people are talking about this. There are many more new information, and many people are supporting and defending,” She responded, “Yes, that is why I don’t like watching the soaps on TV. I like the news better, like Mata Najwa in MetroTV. I am following Munir’s case.”

She then asked me, “Oh dear, Ayie, are you not tired, continuously thinking about this?” I laughed out loud, not knowing what to answer.

Actually my grandmother’s story made me wanted to do a simple research about her younger siblings. But my time limits my choice of concentration. I choose to focus on helping my friends in Papua, because there are so few that are doing this.

I see the position Papua since ’63 as similar to ’65: the destructive power over generations, the stigma, the victims. Both are the historical sins of the founders of Indonesia-post-’65.

Zely Ariane

#1965setiaphari #living1965

When I go to Sleep at Night

But that was not the first time I felt close to 1965 – the first time was actually when Sulami was still alive. It was 2003. I was a crew of a small documentary film about the role of the Golkar party in the events of ’65. We interviewed a few survivors.

Sulami was already having difficulties walking. The director asked her to recount the physical tortures she had to endure. The stories flowed quite slowly, but clearly, from her mouth. Her face looked undisturbed, with no expression. She sighed a lot. She said, “I feel that it is hard to forget, hard to forget,” which then became the title of the short version of the documentary film.

When Sulami left for her room, I helped and lift her. I didn’t know what to say. I asked her a bit stupidly, “How do you feel now?”

Sulami answered with a bit of a bitter smile, “I feel frightened when I go to sleep at night. I fear that when I wake up, I would wake up in ’65.”

Zely Ariane

#1965setiap hari #living1965

And then, Silence …

“It was the soldiers who butchered those people.”

“Ora mung tentara. Wong-wong sipil sing dikongkon tentara yo akeh sing mateni.”*

“Yes, they were believed as PKI, then were butchered like chicken. Beheaded, then thrown away to the river.”

Such horror, their stories.

I did not know what made them start talking about the horrors. I suspect that this was triggered by the recent premiere of the film Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI in the cinemas, which not long after was also broadcast on TVRI, the one and only television channel in Indonesia back then, broadcast by the government. I remember I and my fellow students were brought by our teachers to watch that film in the cinema theatre. I also remembered how quite a few times I had to close my eyes with my hands because of the bloodbath scenes full of violence.

I remember the little me then viewed PKI as something that was very scary. I often quietly watched one of my neighbours, Mr X, whom I heard was somewhat involved with PKI, as though any second he could suddenly pull a sharp item out and kill everyone cold-bloodedly. What puzzled me was, both my parents were always friendly with Mr X. They even chatted like very close friends. When I asked my parents why they were friends with Mr X who was a PKI, their answer was not long, “So what if he’s a PKI? Mr X is a good man.”

I was confused.

When I heard the horror stories about the river becoming red of blood in that back room, which quite a few people admitted seeing with their own eyes, I could not help asking,

“So which of these people are actually the evil ones?”

They who heard my question could only stare at one another. There was no clear answer. A while later, the room was again silent. The noise of the sewing machines continued to fill the room.

And that question that I asked in the 80s was one of my initial questions that gradually piled up in the coming years, on the truth and lies of history devised by the New Order about PKI and 1965.

Sari Safitri Mohan

#1965setiaphari #living1965

* In Javanese: “Not only the soldiers. Many civilians were also killing, as instructed by the soldiers.”

I Did Not Know His Name

My parents rarely spoke about my maternal grandfather. All that was ever said about him was that he simply passed away before my birth. For most of my life, that was all I ever knew about him. I didn’t know his name, I had never seen a picture of him and it seemed like he had never existed.

Several years ago, my father and I were discussing the film The Act Of Killing with each other. After a while, I asked him whether we knew anyone who was a victim. It was then that he told me that my maternal grandfather was in fact imprisoned following the events, and that he was released in 1980. I realised then that was the reason why my parents never spoke about him.

I remember going through a lot of emotions at that moment. I was horrified to learn about what had happened to my family. At the same time I felt dismayed as well. How could my parents have not told me this for over twenty years. He was my grandfather, did I not have the right to know about this?

I quickly learned about the intense burden that was thrust upon my grandmother and her children during that time. How their lives were suddenly turned upside down and everything became a struggle. It’s a period in their life that is very painful to remember. And it is not a period that has been approached with dignity. Up to this day, these events are still stigmatized.

Since discovering my grandfather’s fate, I have dedicated myself to learning more about his life, and the ordeals he went through. I am putting this together in the form of an art project which hopefully will dignify these events. However, my family has been content to let the past be the past, rather than opening up old scars. Hopefully in time I can not only open up about these events to people, but to my family as well.

Anonymous

#1965setiaphari #living1965

1965 is About All of Us

Ayu is part of a young generation of Indonesia who used to consider 1965 as something that had no connection with her. A spark in her intellectual journey brought her to a deeper quest about 1965. In her exploration, she found dark traces of her beloved grandfather. Something that she thought so distant turned out to be very close to her. The following is an interview with her conducted by Sari Safitri Mohan.

When was the first time you knew about the history of 1965 different from the New Order’s propaganda?

I knew it when I finished my undergraduate study and during my graduate study. I took a course on peace studies when I was an undergrad and then I worked as the tutor. One of the course materials was about dealing with the past. One of the pasts we talked about was 1965. Every semester we always screened Lexy (Rambadeta)’s film, Mass Grave, which is blatant enough to inform us about 1965. But at that time I saw it as a detached reality from me. 1965 was just an episode in Indonesian history that I thought had nothing to do with me. I also hadn’t consciously tried to search about my history.

In a way, if I think about it again, it’s kind of funny. As a tutor, I helped students to better understand the course material. Some of them even made videos about 1965, and I connected them with my grandfather, an army general, whom I considered a witness of the 1965 history. It’s interesting that, as a major general, his view on 1965 was not black and white. When he answered my friends’ questions, he sounded knowledgeable and could argue well and coherently about Marxism. He could describe elaborately about why Marxism was not applicable in Indonesia by explaining the basis of Marx’s thinkings, materialism, or that religion is the opium of the people. Later I learned that it was a wrong interpretation of Marxism. So, my grandfather was not the type who would accuse right away that, “PKI is wrong!” but he could argue on the ideological level. During my undergraduate years, I was not exposed to books that discussed 1965 in a different way from New Order propaganda. So the knowledge about 1965 is just something that is passed by. My grandfather also had acceptable logical and coherent reasons about why the tragedy occurred. So I didn’t ask further.

When I became a graduate student in America, I initially wanted to learn about refugees. Until one day, there’s a course that studied about Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). The professor asked me: “How about Indonesia? Many people died, right? About 500 thousand to one million. What about Munir?” I never knew about numbers before. The questions from my professor made me curious to find out. What’s interesting was, the course had a final exam where I had to write an MOU that regulated the rights and obligations of a TRC in Indonesia, how it defined crimes, source of funds, management, and etcetera. Because of this intricate and comprehensive final exam, inevitably, I had to do a thorough research. I had to know numbers, what things that had occurred, and the political dynamics, so that I could figure out what kind of TRC format fit for Indonesia. And at this point, I read many things that gradually felt like I just opened a Pandora’s box. At about the same time, Joshua Oppenheimer’s movie, The Act of Killing, was just released. I met people who guided my search. I can say that the search finally defined my graduate study.

At this point, after I knew a lot more throughout 2011-2012, I was wondering about a thing before going home to Indonesia to do research: It was impossible if my family had nothing to do with all this. So, from the search in cognitive level, for academic purpose, my search veered into personal territory.

There were things in my life that I could not find the answers right away. For instance, my mother told me that in the ‘60s, there were times when my grandfather had to give some codes to his family if he needed to go home. They lived in a military barrack in Magelang, which was supposed to be a safe space. Why did he have to give codes to my mother? I also often read books in his workspace at home. In one of the bookshelves, there were books about Mao, Bung Karno’s writings, Tan Malaka, etcetera. “What is this?” was the only thing that crossed my mind at that time.

Fast forward in the ‘90s. I used to live in Bengkulu. My grandfather and his friends had a plantation business there. My dad worked there. When Suharto was toppled, people who lived around the plantation came and demanded their property back and burned the land. Because of this, I moved to Yogya. In a way, this was an unanswered, questionable displacement for me. Why did those people came and burn everything? Why were they so angry and caused me to move to Yogya to start things all over again? There was no answer then.

When I learned about 1965, everything was gradually connected. Knowing that my grandfather was an army general, I had a feeling that he was involved. And I knew later that there were many “red”, communist, groups in Magelang, including the military. It explained why my grandfather had to take over the leadership of the battalion because the commander was red. And of course, after that, my grandfather’s career went uphill, as were the cases with his fellow army officers.

I braved myself to find out about the whereabouts of my grandfather at that time. His name was listed on a website of one battalion as its first commander and his involvement with the anti-communist purge in 1965 was his accomplishment. It made me think about how far he was involved. I also read many books and found the facts about land grabs by the military troops after 1965 that reminded me of my bad experience in 1999 in Bengkulu that forced me to move to Yogyakarta. I was wondering perhaps they were angry because of the land grabbing.

And then I was searching for the data of the plantation and asked my mother. It turned out that the area was indeed a red region. So, the dots were connected. I thought: OK, my grandfather was involved in 1965, and he had a great career since then just like his friends. In the ‘80s, there was a military disunity between those pro and against Suharto. My grandfather was the latter because it had become clear that Suharto was corrupt. My grandfather was supposed to be sent away as an ambassador, but he didn’t want it, and he finally chose to retire early. His friends with longer careers than him invited him to co-own the business plantation I mentioned earlier, on the lands already “owned by the state” where parts of them were from post-1965 land grabs. It had become the root of latent conflicts. The locals always felt that the land was theirs. That’s why when Suharto was not in power anymore; they seized their lands back. They took what they used to have as violently as when the lands taken from them. I witnessed this in 1999 and felt that I was a victim. At this point, I realized that my searching process resulted in something that’s more than just knowing the fact that my grandfather is wrong. I could see how the unsolved tribulations in 1965 had become the setting of violence in 1999.

My grandfather’s role in 1965 was confirmed when I went home to Indonesia for research. He told me that he accepted a list from the Regional Military Command, the Kodam Diponegoro, that contained people’s names to be captured. These people had to be brought to Kodam Diponegoro in Semarang. I asked my grandfather about it in January 2013, when he was already in poor health: “Do you feel guilty?” He was silent for quite a while before finally answered: “But I didn’t kill anyone.” In May 2013, he passed away before I finished my study. That talk became one of our last conversations.

How did you feel when your grandfather answered your question?

My grandfather and I were very close, we were best friends. Imagine your best friend came to you one day and told you one of his buried secrets. The secret was filled with violent memories that had made him nervous, because of feeling guilty and being afraid to be judged at the same time. That’s how I felt about the atmosphere, when I asked my question, and I saw his face changed into sadness. I knew for sure that deep down he was regretful.

What can I do? Of course I could not and didn’t want to keep a distance after I knew what he had done. But I also cannot turn a blind eye to his experience of violence. His honesty is actually what’s been motivating me to work so that the same violence will not be repeated, so that there’s no humanity wrenched – both of victims and perpetrators. I really want to apologize on behalf of my grandfather’s name to all that have experienced violence from the hands of the state or military since 1965. I know that this is not much, and bears no meaning compared to the sufferings that have already happened but I do hope that an apology in individual level could be a start of something meaningful for reconciliation. I know that my grandfather will do the same.

How have the discussions been in your family after you graduated and went back to Indonesia with new knowledge about the events of 1965?

I come from a military family, but there are some who became victims in 1965. This has influenced my mother and my sister to actively learn and read about 1965. There are family members who to this day still question why I studied abroad to learn about 1965. I don’t have any problem with this. If anything, it informs me about how I should go on with my activism about 1965.

So far, excluding my mother, this is my family’s attitude on 1965: we know about it, but do not discuss it.

How do you reflect on your activism on 1965?

If we agree that the state discourse about 1965 has become a hegemony, maybe we are too naive to ask an institution as large as state to apologize. Hegemony occurs when it rules our psyche unconsciously. It is represented in many social institutions and accepted as daily practice without people aware of it. The 1965 discourse has permeated through many forms, from religion, family, education, and etcetera. The discourse has already been too hegemonic, so that on an operational level, when an institution as enormous as state is demanded to apologize about 1965, it could ask back: “What are we apologizing for?” and the discussion would not go anywhere.

What we can do to make this move a forward is by “attacking” that hegemony from all sides. Facilitate a discussion? Ok. Symposium? Ok. Create a website? Ok. Hold an International People’s Tribunal on 1965 (IPT 65)? Ok. But don’t forget about small things too, classrooms for instance. What is taught in the classroom has an effect. Using spaces provided by campuses to explore alternative discourses is equally important. So, perhaps activism on 1965 can start with things seemingly small but plentiful and diverse.

Also, perhaps because peace studies is my academic background, I try to understand that it is really not easy to make people who used to have an all-out conflict with each other to reconcile. Just look at the U.S.A, South Africa, or North Ireland now. There have been peace processes but people still live with prejudices because of the difference of the skin colors, of different religions, or of different political preferences, until now. So, if we want to reconcile, search for truth or justice, perhaps we need to not only talk about the first generation, but also next generations who have been exposed to stereotypes and prejudices and things that perpetuate the violence. That is why, in my opinion, the effort to find solutions about 1965 has to prepare the audience, who are the second and third generation, with sufficient understanding about human rights, peace, and non-violence concepts, so when they are asked to participate in discussions about 1965, they are going to be ready.

Who do you think is supposed to do this groundwork?

Campuses. As a chain breaker of violence, campuses have a vital role. Because on the campus level, the third generation can be introduced to social justice, solidarity, emancipation, human rights, and peace.

How about outside of campus? Who do you think is able to do it?

Anybody. What I’m trying to say is, if we want to discuss about 1965 solutions, it’s not enough to encourage only about the search for truth. There have to be spaces where people are educated to respect the importance of searching for truth. As an example, searching for truth is important to uphold human rights, and then how to train journalists to cover human rights violations. This is vital. And this work cannot be reduced by certain keywords. The work towards reconciliation, truth, and justice has to be done collectively. I consider my job as a lecturer parallel to activism because every time I get the chance, I try to talk and discuss 1965.

What are main challenges in finalizing the 1965 case?

We all want to reconciliation – but what is it? We don’t have an agreed framework. Some have said that reconciliation means sitting together and then apologize to each other. Others sy apologizing has to come together with reparation. And then others say that for the second and third generation, the reparative side of reconciliation is not a top priority anymore. How people imagine reconciliation depends on how they preserve memories. I talked to a former member of Lekra, The Institute for People’s Culture, who knew everything about the organization’s ideology. He said that reconciliation is not just about reparation. But when I asked Klaten farmers about it, they gave me a different answer. For them, reconciliation has to do with raising their economic status. At this level, perhaps we need to talk not only about the truth of 1965, but also about these varied expectations on reconciliation.

And then about memory: which memory we should recognize. When we talk about mass violence, it was always preceded by dehumanization: certain persons are the enemy and have no right to live; which is why they need to be annihilated. But perhaps reconciliation is not only about finding out how they were dehumanized, but also about returning human-ness by recognizing their previous lives. Many 1965 survivors were captured because of their brilliant ideas. In my observation, the discussions about 1965 often revolve around topics on what happened during and after 1965, how violence occurred, or how victims were tortured. These are important issues to talk about, but to be able to make the second and third generations think about how we have lost something so valuable, we need to know who the victims were before 1965. Some of them were teachers that had brilliant ideas about education in Indonesia. The victims of 1965 were actually the first literate generation of Indonesia. They were students, teachers, doctors, lawyers, first lecturers in Indonesia. Imagine how precious they were. But the way we discuss 1965 is still to the extent of what and how their rights were violated. We haven’t reflected yet on what we have lost.

The framework of truth is a dichotomy of victims and perpetrators. But don’t forget about those who cannot be put in those categories, about those people who were not directly involved but nonetheless affected because of the hegemony of dominant discourse, or because they are relatives of 1965 victims. I think that there still are insufficient initiatives that reach out to this group.

Finally, reconciliation processes depends on one’s capability to be open, inclusive, and to think critically. If an effort to encourage reconciliation is separate from the initiatives that support openness, inclusivity, the understanding of human rights, or critical thinking, it’s going to be a difficult process. Because we will always face the denial of the masses that do not have desires, or perhaps capabilities, to process new information.

In your opinion, why are efforts to remember 1965 – through film screenings or discussions as examples – sometimes dismissed or even met with raids?

When the discourse of reconciliation is released, the second and third generations are those at stake. They have been living with their prejudices. Knowing what happened in the past needs a long process of contemplation about their experiences. Every raid has its masses. Why are these still popular? Well, perhaps because they have spent their lives in the context provided and built by the New Order. They don’t see 1965 as a political conflict but they put it in a narrative of good versus evil. Such an approach is supported by the fact that many people don’t know about it, or aware of it but choose to ignore it when a raid occurs.

What do we have now as an asset to move forward about 1965?

First of all, I think we have tech-savvy and enthusiastic young people. Also, our elites now are busy with their own problems. We can take an advantage from this rupture. As long as we know how to do activism while paying attention to a not-too-stern frame on the topics of 1965, we can utilize those to our benefits. The focus should be more on how to make a movement that can give solutions to 1965 problems that are not only owned by or concerning with just victims and perpetrators, but owned by and involving every Indonesian. It is because we have lost too much. Not only people or family members but also humanity, practices, values, even alternative ideas about how to manage this country.

#living1965 #1965setiaphari

Sari Safitri Mohan

Jugs of Water and Mercurochrome

There was no crack in this neat narrative, until that afternoon, the first Eid after the fall of Suharto. That time, sitting on the steps in front of my grandmother’s house on Bekonang’s main street (a stone’s throw from the local landmark Tugu Bekonang), one of my cousins who was much older than me (my grandmother had 11 children and my mother was born somewhere in the middle of that lineup) said, out of the blue, half absentmindedly, half addressing me, and in Javanese, “Grandmother used to stop the PKI people on their way to be slaughtered, to take a break, right here on this terrace.” “What? Really?” I said. “Yes, she would give them hot sweet tea and mercurochrome for their wounds. She used to run a small drugstore.” “Really? She wasn’t afraid?” “She wasn’t. Sometimes she told me to give them the tea. The mercurochrome, she used to do that herself.” My cousin said she had once said to my grandmother, “I don’t know why you’re helping them, Gran, they’re evil people.” According to my cousin, my grandmother’s cool answer to her question, in the original low Javanese, was: “Uwong-uwong kuwi yo isih uwong, ben do ngerti isih ono sing nggatekke.” (“Those people are still human, I want them to know that someone still cares.”) I was suprised to hear my cousin tell her story. Or perhaps I wasn’t. I’ve read and heard that many people were slaughtered in Bekonang, right on the banks of the Bengawan Solo River. I read of one massacre in one of Martin Aleida’s “witness lit” stories, which was set in Mojo Village and Laban Village on the banks of Bengawan Solo — location names that I used to think were fictional, like Ahmad Tohari’s “Dukuh Paruk”, but turned out to be real. But my cousin’s story also shook me up a bit, because before the fall of Suharto, this story was never told, never even alluded to — now it felt to me my grandmother, who had raised me as well, was a totally different person. Everyone, including me, had always thought that my soft-spoken, quiet grandmother was also anti-PKI, especially because her husband belonged to the Masyumi — PKI’s nemesis — and was once jailed apparently after a dispute with the communists. That afternoon, cracks started to appear in my family’s Orde Baru narrative. Curious, I asked my mum to see whether my cousin’s story was true. My mum is also very Islamic, and often told me, teary-eyed, how she had to bring food to my grandfather in jail, remember, sent to prison just because he was a Masyumi. But she enthusiastically confirmed that my cousin’s story was indeed true. Her story was the same, with a few different details. In her story, my grandmother did not serve hot sweet tea to the PKI prisoners, but water in three big clay jugs that she left on the terrace, and refilled after they were empty. Also, that my grandmother would only help the prisoners in the afternoon, when her husband (my grandpa the Masyumi) was still at the office. She also said that the prisoners were not always marched on foot past our house, but were often piled in a truck and dropped off at the house right next to my grandfather’s house, which was converted into a military base, while waiting for other prisoners to come. Sometimes they would be kept there overnight, sometimes longer. Once their captors thought there were enough prisoners to be killed then they would be sent in the same trucks to the killing field. My mum told me not all of the victims were slaughtered on the banks of the Bengawan Solo, some were executed in the rubber forests near Polokarto. Once, my mum also asked why my grandmother had decided to help these people, who were already on their way to death. Her answer, my mum told me, was, “I feel sorry for them, they must be thirsty. When you see a thirsty person, you have to offer them drink, give them water.” My grandmother never actually told my mum or my cousin what was going to happen to those prisoners — but my mum and my cousin found out on their own. My mum said she had been to the banks of the Bengawan Solo. She said what stuck in her mind was not the bodies that were floating on the water, but their smell. Until now, these stories never got told in front of the whole family. But different family members, mostly aunts, would tell me in details their own versions if I ask them individually. And somehow, for no apparent reason, except maybe that now Suharto is gone, my uncle had also stopped telling his legendary story. Maybe one day I will ask him as well about how my grandmother had helped the people he used to say he helped to kill.

Mikael Johani

#1965setiaphari #living1965

I Want Them To Be Here

In 1965, they were captured in the same month, November 1965. D.A. Santosa was held in Semarang, tried in Cilacap and sentenced to twenty years imprisonment. Boentardjo was held in Wirogunan, Yogyakarta, and never returned after he disappeared sometime between February and April 1966.

Their freedom was taken because they were accused of rebelling against the lawful government. Subsequently that government was overthrown because it was said to be involved in the events of 1965. There is no logical reason for what happened during the 1965 Tragedy and afterwards.

I am telling the story of D. A. Santosa and Boentardjo Amaroen because history can never be concealed. Because I want them to be here, in my life, with my family and my friends. And because they are my grandfathers.

Danang Sutasoma

#1965setiaphari #living1965